A new film by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Winner of the Palme d'Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.

Film and Video

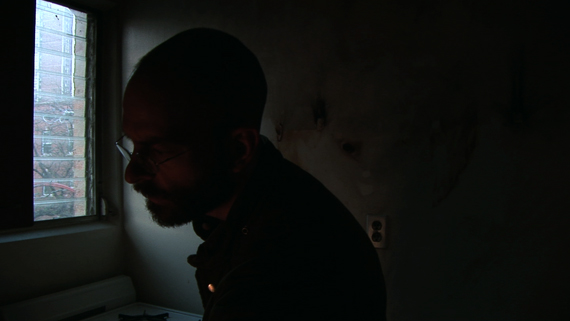

NEW VIDEO POSTED: YX

YX is an allegory about cities, bodies, fluid media, privation and loss, in which hermetic spaces create hermetic narratives. Shot in 2007 in Chicago with performances by Evan Scott Rubin and Jeff Harms, production assistance by Sam Wagster, Britt Willey, Matthew Kellard, Chris Vlasses and Lizzy Lynette Vlasses. Music by Vaughan Williams and Paysage d'hiver.

You can also view the full page with stills here.

Godard's "Socialisme" Trailer(s)

Six trailers for Socialisme, the director’s submission for the “Un Certain Regard” category at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.

Work In Progress: yx

In 2007 I shot ten scenes for a feature length project called The Upper Air, but I was dissapointed with the results and scrapped the project. I've decided to re-edit the scenes into a short entitled yx, which will hopefully be finished next month. The themes and concept are very much the same as the original project: the privitization of resources and of bodies, the translation of hermetic spaces into hermetic narratives, allegories of ecologies in crisis. The new title comes from Stéphane Mallarmé's poem, Sonnet en -yx. The video has performances by Jeff Harms and Evan Rubin, and Sam Wagster was an immense help in the production. Below are some stills from the edit in progress.

De Artificiali Perspectiva

De Artificiali Perspectiva, or Anamorphosis (1991)

Directed by The Brothers Quay

Animation techniques are used to elucidate anamophosis, a method of depiction that uses the rules of perspective to systematically distort an image. When looked at from a different angle or in a curved mirror, the distorted image appears normal. Using animation of three-dimensional objects, the filmmakers demonstrate the basic effects of anamorphosis and reveal the hidden meanings that lurk within selected works of art, including a chair by Jean François Nicéron (c.1638), an anonymous painting of saints (c.1550), the fresco "Saint Francis of Paola" (1642) by Emmanuel Maignan in the cloister of Santa Trinità in Rome, and the painting "The Ambassadors" (1533) by Hans Holbein the younger.

Aesthetics of Microfluidics, Part 1

I am interested in the extended and recontextualized meanings of industrial media, as a possible mirror image of the media industry. This short video by Formulatrix demonstrates their product, "the Formulator", and its "microfluidic chip dispensing a 96-well plate".

Thirdworld

Thirdworld (1998)

Director: Apichatpong Weerasethakul

"This film depicts landscapes, metaphorically and actuality, of the southern island called Panyi. It reflects the impression of the shooting time at the island for several days. The sounds are taken from different sources, but all were recorded while the subjects were not aware of the recording apparatus. Thus, this piece may be called a re-constructed documentary. The title is intended as a parody of the word that is being used by the West to describe Thailand or other exotic landscapes. This film is the voice from individuals who reside in such environment. The film is presented in crude and rugged quality, as it is a product from the uncivilized."

— Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Letters from Fontainhas

I cannot overstate the importance of Pedro Costa in film history or current global cinema — nor can I here sum up the importance of these three films which are being given a long overdue US release by Criterion this month. Suffice it to say that many critics have said that Costa has reinvented every aspect of filmmaking and has created completely singular, honest and beautiful works since his earliest films on 35mm to his latest landmark DV pieces.

I cannot overstate the importance of Pedro Costa in film history or current global cinema — nor can I here sum up the importance of these three films which are being given a long overdue US release by Criterion this month. Suffice it to say that many critics have said that Costa has reinvented every aspect of filmmaking and has created completely singular, honest and beautiful works since his earliest films on 35mm to his latest landmark DV pieces.

In discussing the earliest of these three films, Ossos (1997), Costa himself as well as many critics are preoccupied by discussing the failures of a traditional 35mm film production in acheiving the filmmaker's goal of blending into the environment of the real Lisbon neighborhood of Fontainhas and preserving the texture and natural quality of the residents and performers — all issues which Costa goes on to dramatically address in his subsequent DV films. However, the fact remains that if not viewed in comparison to Costa's subsequent films but all precedent film history, Ossos is an undeniable masterpiece of naturalism, realism, and the rarely attempted or successful project of creating films that are simultaneously poetic and political. Shot by the brilliant cinematographer Emmanuel Machuel (L'argent, Um Filme Falado, Casa de Lava) in liminal greys, blues and blacks with almost no artificial lighting, the film inhabits the damaged and painful lives of the residents of Fontainhas through a revolutionary collaborative and self-aware artifice of style and structure.

But this was not enough for Costa, who was compelled to become a resident of the Fontainhas and generate the material with the performers in an organic yet imaginitive two-year process that became the unprecedented masterpiece, No Quarto da Vanda (2000). While completely eschewing the institutionalized practices of film production — shooting without lights, script, actors, crew, or even a noticible division between filmmaker and subject — Costa elevates the most impoverished material to the emotional and visual tenor of high-renaissance painting through what I consider the most original and talented "eye" in cinema today. This is a cinema whose great depths of meaning and heights of intent are only made possible through the divestment of power structures and official culture — which, for my money, is the most important kind of filmmaking happening in the world today.

Juventude em Marcha (2006) takes this progression into a third, reflective and elegaic phase, treating the collaboratve construction of this narrative space within the real physical locations of their neighborhoods as an an epic meta-text of the everyday that is equally psychological, poetic and political. In an extraordinary technical and aesthetic feat, Costa ramps up the symbolic grandeur of the characters while simultaneously heightening the alienating self-referential stylistic elements: what was the near lack of film lighting in Ossos, then the total lack in Vanda, is in Juventude an ecstatic use of DIY expressionistic and highly stylized film lighting acheived by the use of many pieces of reflective materials and mirrored surfaces, bouncing and cutting the natural light into eye-popping tableaus. Juventude puts institutionalized commercial film production methods to shame twice over: the honesty and poverty of his production methods proudly become integral to and involved in the meaning of the film at the same time that he is creating images far more innovative and stunning than the biggest-budgeted, hi-tech films currently being made.

Some have likened what Costa has done in this trilogy to the development of abstract expressionism in painting — which I would have to disagree with given that movement's all-too-comfortable repurposing as corporate lobby decoration. If I had to find an analogy in traditional high-artistic media, I would say that Costa has done to film something like what Samuel Beckett did to the novel in his famous trilogy — stripped of institutionalized and commercial techniques, infusing dazzling gestures of prosity with what was before hidden from view by established codes of representation, the work of generating radical subjectivity can begin — if we seek it out. You can order (or pre-order) the box set from the Criterion website.

Yusuf Üçlemesi (Yusuf's Trilogy)

Trailers for three films by Semih Kaplanoğlu: Bal (Honey), Süt (Milk), Yumurta (Egg):

Praising with Faint Damnation: the Critical Response to "Inglourious Basterds"

(This entry is reposted from my old blog, Decorporation Notes - September 7th, 2009.)

I’m afraid that in the admirable quest for a subject of cinematic criticism, we’ve settled instead on a suitable subject for the criticism of mass spectacle.

The conspicuous success and consumption of Tarantino’s media events is certainly worth discussing, but to do so in terms of cinematic intent is like discussing the acting technique of a ventriloquist’s dummy: Tarantino has succeeded in pantomiming meaning with enough unconsciousness to suspend the audience’s and critic’s disbelief long enough for them to believe they are watching a film — but so, for that matter, did WALL-E. If we actually believe a single frame of Tarantino to be intentional, where, then, were the moral debates over his use of Samurai history in Kill Bill? The attention drawn to the very difficult lives of real undercover law enforcement agents following the release of Reservoir Dogs?

The impersonation of cinemaWhat better way to attract critical attention that to convincingly pantomime the film genre that is ostensibly concerned with the greatest moral problems of humanity? In terms of cinema, I believe the equation in Inglourious Basterds is boringly simple: Tarantino has merely shifted his aspirations in the decidedly horizontal spectrum of establishment positions — and he is celebrated winkingly for his un-self-conscious ability to regurgitate formulas of dialog, plot, camera movement and montage, and, of course, his complete lack of any compunction towards the deepest cynicisms of his age

The impersonation of cinemaWhat better way to attract critical attention that to convincingly pantomime the film genre that is ostensibly concerned with the greatest moral problems of humanity? In terms of cinema, I believe the equation in Inglourious Basterds is boringly simple: Tarantino has merely shifted his aspirations in the decidedly horizontal spectrum of establishment positions — and he is celebrated winkingly for his un-self-conscious ability to regurgitate formulas of dialog, plot, camera movement and montage, and, of course, his complete lack of any compunction towards the deepest cynicisms of his age

It is fascile to analyze the events of the funding, production, distribution, marketing and mass viewing of this strip of celluloid without bringing to bear the economic and social mechanisms that allow for such things to happen, and which profit by them. And in this regard, to single out this film for critique on the basis of it’s historical content is to believe that the filmmakers, actors, cinematographers, art directors et cetera actually meant “Nazi” when they uttered the word, made the costume, or wrote the press release. The so-called “inversion” or “rewriting” of history in the plot might be worth discussing if the filmmakers were intending or even capable of referencing reality instead of titilating themselves and the audience with their willingness to destroy understanding and meaning through their reflexive reflexivity. Reviewers may wish to discuss the “fantasy” of Jewish people taking revenge on living Nazis — going along, as it were, with the joke: the Nazis and Jews being pantomimed here could be replaced with any aggressors and victims of historical incident, granted that the history is still politically or emotionally charged enough to illicit post-ironic glee in its dismissal as a purely rhetorical device.

The real fantasy, I feel the need to quip, is the idea of audiences encountering a film in the cinema that actually deals with the moral, ethical, political or emotional problematics of the Jewish (or any other) genocide and its representation. Of course, such fantastic films are very real, just not commonly given value or representation in the mass media. In avoiding the discussion of such films, I can only conclude that reviewers are skirting the much more complex matter (not reducible to upturned thumbs or a star-based quantification scheme) of why and how certain objects of mass spectacle arise, are given pseudo-critical attention, and praised with faint damnation.

Therefore (surely you saw this coming) the most glaring oversight in any discussion of Inglourious Basterds is the figure of Jean-Luc Godard, recognized as the filmmaker most preoccupied with the holocaust — presumably because to enter into the complex cinematic significance of the Histoire(s) or In Praise of Love would be to remove the irresistible shininess of the glare of mass spectacle from this slight, pathetic and barely-willed piece of fake-blood-strewn shit Tarantino has most recently withered from his hyperactive anus. I shivered as I saw once again, the words “A BAND APART” appear at the beginning of Basterds, and was reminded of the quote by Godard, “Tarantino named his production company after one of my films. He would have done better to give me some money.”

Here are some more fantasies: perhaps the budget of Basterds should have gone towards the American broadcast or distribution of the Histoire(s). The thesis of Godard’s Histoire(s), it has been many times said, is that the history of film, and in some extension, mass media, has been forever changed by it’s failure to show the atrocities of the camps while they were operating. I am tempted to give Tarantino the credit of reinvigorating this failure for a generation who is already ignorant of it’s historical antecedents (filmic and moral) — but again, I would still be participating in the pantomime. The primary moral dilemmas on display in the theater on the night I saw Basterds concerned the valuation of art in America.

Pop formalism being the order of the day — fascinating critics and mass audiences alike — we can all masochistically applaud the death of film culture presented to us in the beige, recycled composites of the International New Waves via the American “Mavericks” (There Will Be Blood, No Country for Old Men) or the callous (and sometimes bigoted) reduction of social allegory to an easily subvertible, vapid genre technique (Slumdog Millionaire, District 9). In this climate, I see very little to be remarked upon in Basterds as a film, or Tarantino as a filmmaker — the “self-reflexivity” and “genre-blending” he utilizes is as remarkable as his use of color film or sound. Why, however, we believe that it is to be considered a film at all — a discrete object of culture — is worth discussing. And in that discussion, perhaps his faint damnation of war criminals could be adequately reviled.

"The Headless Woman" by Lucretia Martel

It has often been said by film critics and enthusiasts that the decision to not show something disturbing or violent on screen can be more powerful than showing it — a cinematic or cinematographic equivalent of formal limitations in prose — and this is most commonly said of horror films. The ability of the limited frame, the minimal score, the inclusion of darkness and silence in the mise-en-scène to inspire the viewers imagination to generate genuine terror is limitless, as evidenced in the most disturbing moments of Hitchcock, Lynch, Bergman, and too many others to name. There is a common purpose between such techniques and the famous technical limitations of Bresson and Ozu (and their acolytes) — Bresson’s insistence on a single focal length for an entire film, Ozu’s regimented camera placement to reflect the point of view of a child (or Kubrick’s in The Shining, for that matter) — and it can be described as an attempt at radical subjectivity. In a period of film that is seemingly divided between the festival-adored self-reflexive spectacularism and shock of the Hanneke school (exemplified by the extraordinarily vapid Mexican film Los Bastardos of last year) on the one hand, and the Hollywood fetishism of the virtual, omnipotent and omnipresent camera, Lucrecia Martel’s exploration and development of the techniques of restraint and radical subjectivity are more than a breath of fresh air—they display the limitless psychological power of fundamentals of cinema: lights, camera, sound and action.

The Headless Woman is a sort of fever dream — the structure of the film creates a sensation of trauma and disorientation through a number of extraordinary means. The film opens with an intriguing scene of some kids playing with their dog, midway on some small adventure through the canals and dusty hillsides on the outskirts of an Argentinian city. There is tension in this very first scene as the kids climb rickety metal structures and cart-wheel into cement canals recklessly, yet as naturally as all pre-adolescents do. We then get a brief glimpse of the small society of bourgeois women that is the filmmakers primary concern, wrangling their young children, airing their concerns about a new pool being built and discussing upcoming social plans. In this scene, not five minutes into the film, we are already affronted with Martel’s full power as a filmmaker adept at evoking an immersive, natural atmosphere and keeping us fascinated with it while not being able to make any cohesive picture out of it. She gives us tiny, fleeting details that we remember for the rest of the film by framing them in arresting moments — of afternoon light catching the oily fingerprints of a child on a car window, for instance. In this overload of sensory information there is still a perfectly natural scene being depicted, but we are aware of the filmmaker crafting a thematic development through the edits and sound mix, always surprising us with frame after frame that we could not have expected but nonetheless develops the logic that permeates the entire film.

And thus, before we have been given any comfortable context or background to settle into, we are caught off-guard by the central event of the film: Vero, the character whose subjective experiences the film traces, is driving on the road along the canal and, in a moment of distraction caused by her cell phone, hits something. As with all of the violence in the film, this occurs off screen, and we watch Vero’s face as she quietly makes the decision to continue driving. We see, out of focus and far in the distance behind her car, the dog from the first scene lying in the road. This event coincides with the beginning of a violent storm, one which washes away the traces of the accident, along with Vero’s identity. Later, when Vero returns home, she is frightened by the entrance of her husband carrying the carcass of a deer he has killed while hunting.

Throughout the film, the frame is almost always placed in close, uncomfortable proximity to the main character Vero, and we watch her navigate a world she appears to be confused by and lost in — a world which is often shown only as an out-of-focus blur. This type of close-up is contrasted with Martel’s other recurring technique of creating planes of action in the frame, separated by walls, windows, fabrics and other screens. While the latter is reminiscent of some of Jean-Luc Godard or Chantal Akerman’s latest work (Detective or The Captive, especially), Martel has in these cinematagraphic forms developed a subjective means to explore control that is distinct from the famous static, presentational wides of Ackerman or late Bresson. Nonetheless, Martel clearly evokes the tragic figure of Jeanne Dielman in the meticulous colors and style of her leading lady’s accoutrements — like Akerman, Martel is extremely interested in the lives of mothers, who have an especially significant presence in the recent history of Argentina. Vero’s daughter, in her late teens or early twenties and suffering visibly from hepatitis, attempts to illicit genuine affection from her mother, who seems to treat all affection with a generic pleasantness and can give nothing other than her detached and vacant smile.

Of course, we cannot forget sound when talking about Martel’s films. The Holy Girl is one of the only films in recent memory that utilizes the full potential of naturalistic sound recording and mixing (Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Tropical Malady being, for me, the other most noteworthy example of the last decade). In The Holy Girl, as well as in The Headless Woman, Martel is able to use the creation of a layered, subtly shifting sonic atmosphere to construct a mode of subjectivity — a task for which most filmmakers rely solely upon lighting and camera placement.

The dialog and the character’s reactions never make clear to what extent Vero remembers who she is or knows what is going on around her. When she runs into her husband’s cousin in a hotel restaurant after the accident, it is not clear if she recognizes him or is politely smiling and merely seeks the comfort of another human being. As she sleeps with him, navigates her way to a hospital, and finally makes her way home, the editing recalls the familiar film grammar of a series of recalled events, a reconstruction, and the film feels like a puzzle. The clues are in the tiniest gestures, and are often completely overshadowed by the overbearing hum of an electrical light, or startling city noises. Like the victim of a stroke or seizure, the reality of the film which Vero is navigating has become unweighted, all details have become equally and overwhelmingly disturbing, and there are no clear signifiers.

This neutrality gives us and Vero the opportunity to look at the structure of her life with newly detatched eyes, and the rest of the film is concerned with her realization and confession that she may have hit a child on the road, and the way in which the men in her life react to this. We follow Vero as she retraces the events of that day and her husband and his cousin have erased all traces of her stay at the hospital or the hotel, enacting a conspiracy to protect her from the world and herself. There are clues that she may have in fact killed a child, as we learn that one of the boys who works at a landscaping shop in the poorer outskirts has gone missing. We watch the back of Vero and her family’s heads as they slow in their car to watch the canal being excavated for whatever was washed in during the storm and has blocked the drain. As the men in Vero’s life erase the traces of that day they erase the possible truth of what happened to the child, and Vero’s connection to reality. This theme is given dominance and formal resonance in the film’s closing shot — Vero is greeted and hugged as she enters a large family gathering, only visible through tinted and distorting glass.

Vero’s complete disregard of her servants and the stark contrast between the lifestyles of Vero’s family with that of the impoverished neighborhoods on the outskirts of the town are important motifs that illustrate Martel’s implication of class structures in the types of social pressures that create “headless women”, and which condone the disappearance of children. Leslie Helperin, in her Variety write-up, remarks:

Despite the guilt theme, thesp Onetto keeps Vero’s signs of anxiety so subtle she almost doesn’t seem all that bothered. Maybe she’s not, and maybe that’s the point, but if this is a work of social criticism, indicting the callousness of the rich, it’s pretty mild stuff.

Stephen Holden in The New York Times writes:

You could say “The Headless Woman” is a meditation on Argentina’s historical memory. It subtly compares Verónica’s silent disavowal of responsibility for any crime she might have committed with that country’s silence during its dictatorship, when suspected dissidents disappeared. In interviews Ms. Martel has suggested that “The Headless Woman” is about Argentina’s refusal to acknowledge a widening economic disparity between the middle and lower class. And the scenes of light-skinned Argentine bourgeoisie interacting with darker-skinned workers suggest that the two classes are mostly invisible to each other.

Both writers believe that the references to Argentina’s history and class politics is subtle, mild, or vague. However, Martel manages to seamlessly incorporate political metaphors and realities into her films, and in The Headless Woman this is done partially through a deep psychological symmetry that echoes aspects of Argentina’s recent past — highlighting the deep impact of the violence and mass disappearances of the late seventies and early eighties. It is no accident that the film’s art direction is evocative of this period and thus of the many Argentine films that depict that period.

Filmed, like her other films, on location in the region of Argentina in which the director was born and raised, the characters of Vero and her daughter are roughly the ages that Martel and her own mother would have been during this period. The figure of the mother in relationship to Argentina’s history has been continually made important by the Mothers of the Plaza del Mayo, an association of Argentine mothers whose children were forcefully disappeared during the Dirty War the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1983, and who have demanded the official records be made public for over thirty years. These issues remain vital and political, at the very least to Argentinian audiences. While it is not by any stretch of the imagination a historical retelling or expository work of social realism, as a reflexive meditation on the difficulties of constructing an identity when recollection is distorted by trauma and prohibited by institutionalized power structures, this film could not be more direct, personal or powerful.